This American Photographer Tirelessly Advocated the Idea Photography Is an Art

From Photo-Secession to 291

There is an old question, what came first, the chicken or the egg? For the history of photography, the question can be re-written: what come up first Camera Piece of work, the journalistic organ for the Photo-Secession or Photo-Secession itself? The unexpected respond is that Camera Piece of work came into existence commencement, as a publication designed to promote American Pictorialism, and the actual organization itself emerged out of the joint ambitions of Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), tireless promotor of the idea that photography was fine art and artist and photographer, Edward Steichen (1879-1973). Although both photographers had long and very divergent careers as artists, it was Stieglitz who was the entrepreneur and crusader, while Steichen often provided the inspiration and guidance that prodded the American's sensibility towards the avant-garde. The 2 men worked together in stages, with Stieglitz, the older homo, taking the outset step and Steichen, his protégée, urging the adjacent motility.

Alfred Stieglitz.Wet Twenty-four hours on the Boulevard (1894)

If Alfred Stieglitz was famous for anything, it was his role as the American who led American art and artists, pace by unwilling stride, into the twentieth century. As he said, "I was built-in in Hoboken. I am an American. Photography is my passion. The search for Truth my Obsession." Just, as the son of immigrants, he was educated in Europe and embellished his studies in Berlin with travels to the various art communities on the continent. When he returned to New York, his home town, Stieglitz was uniquely positioned to infiltrate and influence the minor elitist earth of amateur photographers of his abode town and other cities on the Due east Declension, such as Philadelphia, towards taking more than decisive and radical steps every bit "artists." For many amateur photographers in New York, mirroring the attitudes of their English counterparts, shifting their piece of work and individual identities from hobbyists sharing noesis about techniques to defended and professional person artists was a span too far. Stieglitz abandoned his efforts with the Camera Club of New York and its in-business firm publication he had nourished, Camera Notes, in 1902, for his ain contained publication Camera Work. While Camera Notes was a magazine dedicated to reporting on and discussing and illustrating fine art photography, Camera Work was more focused, featuring high-level art writing about aesthetics and the advanced, past authors such every bit George Bernard Shaw, (Carl) Sadakichi Hartmann, and Gertrude Stein. Dedicated to press works of photographic art beautifully in a beautiful setting and caput of its time, Photographic camera Work predated the kind of publications for photographers all the same favored today–elegantly printed reproductions of images in a format, the anthology or book, that allowed the photographer to control the distribution of his or her piece of work. Only, on the other paw, the publication besides resembled the very poplar photographic albums of the time, issued in express editions past the artists, often accompanied by short texts for each epitome.

Subscription for Camera Work

What made Photographic camera Work unique was its exclusive focus on art photography with its hand-tipped positives or photogravures printed on Japan (tissue) paper and secured in place with a mat. Press a photograph was considered an fine art course and the journal always acknowledged the work of the printers. It seems that in the early years of the new century, Stieglitz was pausing from his crusade and his attempts to convert large groups of people, perchance consolidating his gains, and gathering his adherents, such as international prize-winner Gertrude Käsebier (1852–1934), into an informal group, Photo-Secession. Although many of the photographers who "showed" in Camera Work, such every bit French artist, Robert Demachy, were Pictorialists who manipulated their images, Käsebier was an early on "straight" photographer who did not manipulate her work. In improver to promoting the Photo-Secession as a permanent grouping–one could become a member for a mere v dollars–Stieglitz was eyeing the international activities amongst art photographers in Federal republic of germany and England, where he was recognized as a leader in the field. Indeed, he was in Germany again in 1904, feeling afloat and exhausted, merely as he examined the field of art photography, Stieglitz began to formulate a vision, not for his next step, but for art photography as well. Photography needed to be rescued from the excesses of Pictorialism. The new direction was suggested by a immature photographer, now a favorite of Stieglitz, Edward Steichen.

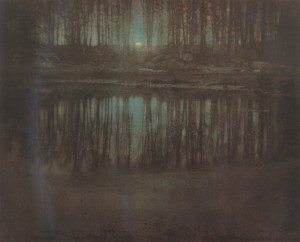

Edward Steichen. The Pond–Moonlight (1904)

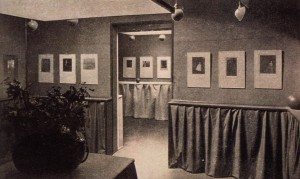

In 1902, when Steichen returned to New York after years of report in Paris, he quickly realized that Camera Work and its reputation for presenting contemporary perspectives on photography could exist a platform from which a new organization could be launched and he too recognized that this organisation needed a identify to exhibit. Steichen had a studio at 291 Fifth Avenue, and in 1905, he offered the modest rooms to Stieglitz as a identify to testify selected images from the Photo-Secession group. Every bit European-educated Americans, the ii photographers had learned from previous exhibitions of photography, peculiarly in London, where James Whistler was revolutionizing the art of art installation, In 2004, the Freer Gallery held an exhibition,Mr. Whistler'due south Galleries: Avant-garde in Victorian London, to celebrate the creative person's exceptional vision of how art should be exhibited. Whistler controlled the exhibiting and display of his ain work when he could. In discussing "'Arrangement in White and Xanthous,' and 'Organization in Mankind Color and Gray,' two of Whistler'due south most famous and influential installations and examines his role in the forefront of exhibition design," the museum stated that "Both installations were controversial and radically innovative because they challenged long-continuing assumptions about the display of art. Featuring identically framed artworks that were hung widely apart on plain, lightly colored walls in moderately sized but elegantly appointed rooms at a time when exhibitions routinely displayed artwork from floor to ceiling with no space between frames, Whistler'south installations paved the way for the spare exhibitions that have go the norm." In designing the galleries for the Photo-Secession exhibitions, Stieglitz and Steichen followed the precedents set past Whistler twenty years earlier. In fact photo-historian Weston Naef noted that Frederick Evans had followed a like arroyo in his testify at the Dudley Gallery where the Linked Ring artists exhibited and described his color scheme to Stieglitz.

The Fiddling Galleries of the Photo-Secession opened in 1905 with three rooms, busy in earth tones of olive and gray with burlap in the walls, setting off the white-framed photographs which, every bit in Whistler's exhibitions, were shown equally single images hung on the line, at eye level, foregoing the usual salon way of stacked images favored at the Dudley Gallery and following the new arroyo pioneered by Whistler. But the photographers did not have the subtle sense of colour that turned Whistler'due south installations into interior symphonies of tones. In the 2013 volume,The Aesthetics of Matter: Modernism, the Avant-garde and Material Substitution, Lori Cole wrote wryly that "the gallery space itself is recalled as a drab serial of pocket-sized rooms, its unimpressive pallor only worked to heighten its mythic status..which was envisioned as the center of a community committee to advocating goer photography and modern art in America." Photo-Secession exhibitors included Stieglitz and Steichen, Käsebier, Alvin Landon Coburn, Frank Eugene, Clarence White, and other stalwarts of the Pictorialism movement in New York.

In 1906, Steichen designed a beautiful Art Nouveau style affiche for the issue, which in many means, was the high h2o mark for the nineteenth century version of fine art photography. Stieglitz and Steichen had mastered their arts and crafts and their work by this time had reached the heights of personal best, but the fine art world had inverse in Europe. Impressionism, both French and English had been superseded by new movements. Post-Impressionism stressed pattern and composition over visual perception, Art Nouveau concentrated on line and graphic acuity, and a radical new grouping of painters in Paris, the Fauves, suggested that painting was a mere formal vehicle for individual expression, an idea that was communicable on in Frg. Photography had to change in response to these new ideas and it was Steichen who urged Stieglitz towards twentieth century modernism through the modern art of Cézanne, Picasso and Matisse. The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession came to an terminate and the headquarters for modern art in New York City moved and changed its perspective.

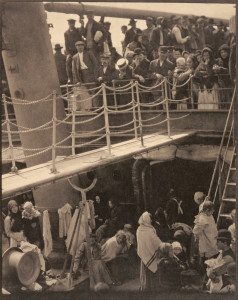

Parenthetically, information technology should exist noted that, amongst the sources consulted on the history of Stieglitz's famous 291 Gallery, there is defoliation every bit to precisely where the gallery was located–in rooms vacated past Steichen or in rooms located across the hall. For the purposes of this website, this post has elected to follow the business relationship of Stieglitz himself in which the Gallery began in the vacated studio and so moved across the hall, under some other name. In any consequence, by 1908, when the "Little Galleries" moved across the hall to a new set of rooms, the shift corresponded with an increased attention toward painting from the earth of the European advanced. To mark the break with the past, the gallery was renamed, make clean and simple and un-confining equally to purpose, after the address: 291. Another change, signaled by the photograph that would come to ascertain Stieglitz, The Steerage (1907), marked the end of Pictorialism and the beginning of directly photography. In earlier years, Stieglitz had admired the "straight" piece of work of Käsebier, but a decade afterward he was a staunch advocate of Paul Strand. The divergence between Käsebier and Strand is not but how they developed their pictures merely in the content or meaning of their photographs. Käsebier created narratives or symbols with her work, placing her firmly within the tenets of Pictorialism and of Symbolism in painting. Strand, in dissimilarity, seemingly returned photography to the sphere of photographic camera vision, but this lensman was not a documentary photographer in the traditional sense of the word, nor was he recording reality for the purpose of nomenclature or accounting for an environs. Like Stieglitz, Strand had come to the determination that a photograph could be "direct" or not manipulated and at the same time, information technology could exist an instrument for pattern. In other words, the insight of James Craig Annan, whose work was exhibited by Stieglitz, that a lensman's heart could seek and find a composition that was formally compelling and capture this moment in time, was the new approach to photography.The Steerageexemplified this new way of making a photo.

As Stieglitz told the story, he and his wife were taking a sea prowl on the ocean liner, the Kaiser Wilhelm II. These modernistic liners were divided into three levels or 3 decks, reflecting the classes, start, second and tertiary, or steerage. It was the steerage passengers who provided the profit margins for the companies when they were ferried to New York. There they passed into the New Earth, through Ellis Isle–or not. It is worth noting in passing that the people photographed by Stieglitz were poor people, peasants and proletariat, being returned to their nation of origin. The U.s. put potential emigrants though a filtering of sorts–no one unhealthy or contagious, no one who was considered a communist or an agitator was immune to stay. Knowing the history that awaited this collection of rejects photographed past Stieglitz, the gimmicky viewer senses the bleak fate awaiting the deck of desperate people. Stieglitz considered none of the grim facts of the scene beneath him, instead, according to his account, what he saw was "A round harbinger chapeau, the funnel leading out, the stairway leaning right, the white drawbridge with its railings made of circular chains,–white suspenders crossing on the back of a human being in the steerage below, round shapes of iron machinery, a mat cutting into the heaven, making a triangular shape.."

Alfred Stieglitz.The Steerage(1907)

In writing about The Steerage in 2012, Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker explained how the photograph transcended its ostensible content and, "becomes about how one practices photography and the promise of that practise..it also first and foremost thematizes the condition of the camera at that particular indicate in time.." Although Stieglitz considered his photo to be his first "modernist" work, the technology was an old fashioned camera with a glass plate. In his excellent 2012 article, "The Prismatic Fragment: Looking into Alfred Stieglitz's 'The Steerage,'" which also appeared inThe Steerage and Alfred Stieglitz, Jason Francisco described the technology, starting with the camera:

"The Graflex: a leather-covered box, turtle-like when closed and crane-like when open. From behind a fitted frontside panel, the lens creeps forwards by the turning of a small knob, lightly knurled for thumb and forefinger, a deliberated conveyance forth a finely cut rack and pinion. The lens is the prized Goertz Double-Anastigmat ("Dagor"), half-dozen inches in focal length, exquisitely precipitous and with a maximum discontinuity of f/6.8, which is to say broad enough make utilize of the Graflex'due south other great advance, its fast shutter speeds—including twelve speeds between one/100th and 1/1000th of a second."

The photographic camera was land of the art, but Stieglitz was one of those sometime-fashioned photographers who resisted the allure of George Eastman's Kodak film and insisted on controlling the development of his own images–hence the glass plate with its sensitive negative. According to his business relationship, he developed the negative in Paris but kept it fixed to the plate until he returned to his familiar surroundings in New York. The design of The Steerage is surely one of the most circuitous of its and of any twenty-four hours. The corresponding motifs are subtle and the design is multilayered, so much and so that the outset person who saw the positive thought that Stieglitz combined two different photographs on 1 plate. In fact, The Steerage is about looking downwards: the viewer/the photographer looks downwardly upon people looking down upon people. But the vertical plunge is broken past a diagonal causeway, bleached white. The trained middle of Stieglitz defenseless, consciously or unconsciously, the correspondence of multiple motifs: the tilted white straw chapeau and the opened spool, the two stripes on the edge of a adult female's shawl and the rope handles on the causeway. The funnel and the stairway open up upwardly the cramped verticality by splaying outward, left and correct. The formal qualities of The Steerage are evident to us today, however, but contemporary reappraisals can be somewhat off the marker. There are those who wish to re-identify the image within the social and political currents of the time, but Stieglitz did not encounter the human tragedy before his eyes. Perhaps because of the coincidence of The Steerage and Les Demoiselles d'Avignon being executed in the same yr, 1907, and because Pablo Picasso admired the photograph, there are those who wish to place the composition within the confines of Cubism, just Cubism and its new visual vocabulary had not yet been invented. That said, like Picasso, Stieglitz was a revolutionary who closed off the doors to the past and open up a new passageway into a new future for photography.

If you take found this material useful, please requite credit to

Dr. Jeanne South. Chiliad. Willette andArt History Unstuffed. Thank you.

[email protected]

sinclairyoupe1966.blogspot.com

Source: https://arthistoryunstuffed.com/photography-as-artart-as-photography/

0 Response to "This American Photographer Tirelessly Advocated the Idea Photography Is an Art"

Post a Comment